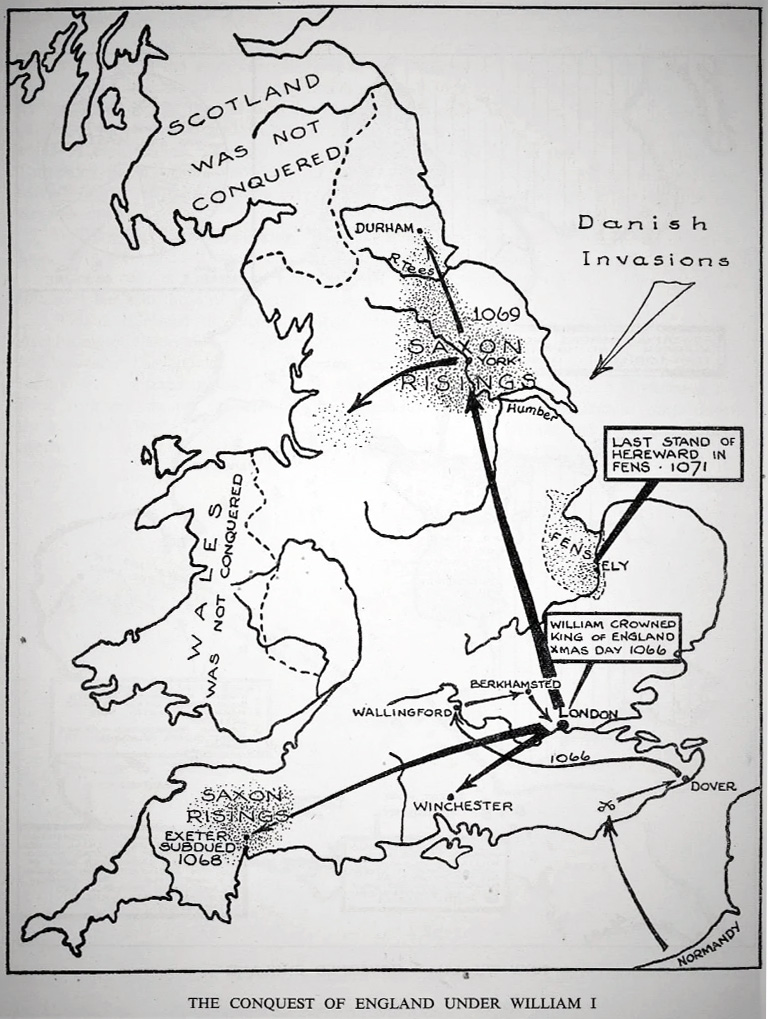

There are numerous occurrences of the 'Gynn' name, or men who would be eventually be named 'Gynn', that seem to correspond to locations where William's armies were present. Berkhamsted is a key site for King William's rise to power and we find the 'Gynn' name appears often in Hertfordsire. There is also a higher number of occurrences in Yorkshire, where King William I sent his army to quell a Saxon rebellion in 1069. The same can be said in 1068, somewhat less so, for southwest England, in Devon and Cornwall.

One such place, Berkhamsted Castle, in Hertfordshire where nearby a number of 'Gynn' residents have been shown to be present in the early medieval period; in Anstey, Aston, Berkhamsted, Hoddesdon, Stevenage, Ware and Welwe, all before 1500. When William's armies overtook the Saxon armies, he used his army 'engineers' in roles such as for the destruction of defences, as well as later rebuilding them for his own purposes. This would have also required stone masons, carpenters and so on.

There are Ginns in the Berkhamsted area to this day.

"There seems little doubt that it was for the purpose of receiving the surrender of the Saxon government that William had the castle of Berkhampstead erected. He probably turned his whole army on to the work of digging the ditches and raising ramparts and motte, and many of the local Saxon peasantry must have been pressed into the work, which could have been completed in a week or so". (1)

"Berkhamsted Castle ... was built to obtain control of a key route between London and the Midlands during the Norman conquest of England in the 11th century. Robert of Mortain, William the Conqueror's half brother, was probably responsible for managing its construction, after which he became the castle's owner.

Chroniclers suggest that the Archbishop of York surrendered to William in Berkhamsted, and William probably ordered the construction of the castle before proceeding south into London.

"By the mid-12th century, the castle had been rebuilt in stone, probably by Becket, with a shell keep and an outer stone wall.

The castle was besieged in 1216 during the civil war between King John and rebellious barons, who were supported by France. It was captured by Prince Louis, the future Louis VIII, who attacked it with siege engines for twenty days, forcing the garrison to surrender, throwing what chroniclers termed innumerable "damnable stones" at the defenders". (2)

"When John died, Edward III reclaimed Berkhamsted Castle [using it] as his main property and investing considerable sums in renovating it.

[In the late 13th century], the town of Berkhamsted itself became rich as a result of the growing wool trade [and] in subsequent years, Berkhamsted then became closely associated with the Earls and Dukes of Cornwall.

Edward, the Black Prince, was created Duke of Cornwall and also made extensive use of the castle, which formed part of the new duchy. The Black Prince took advantage of the aftermath of the Black Death to extend the castle's park. When he fell ill following his campaigning in France, he retired to Berkhamsted and died there in 1376.

"Under Edward the Black Prince, Berkhamsted become a centre of English longbow archery. A decisive factor in the English victory at the Battle of Crécy (1346) was the introduction of this new weapon onto the Western European battlefield." (4) Some Ginns are recorded as being 'archers' including a Richard Gyn in 1373. (See note)

Richard II inherited Berkhamsted Castle in 1377; initially the use of it was given to his favourite, Robert de Vere". (2)

"The military aspect of the castle, however, seems to have been neglected thenceforth, and it is noticeable that no attempt appears to have been made to raise the walls which had proved useless against Louis's siege engines and were obviously by then obsolete. Instead of receiving the lofty curtain walls necessary in the thirteenth century for protection against high-trajectory trebuchets, whatever was done to the castle during this century seems to have been confined to its domestic buildings". (5)

"Although frustratingly short on detail, the delayed pipe roll accounts made by Robert de Stuteville, sheriff of Yorkshire, and Ranulf de Glanville, custodian of the honour of Lancaster and the honour of Conan earl of Richmond, reveal just how important, in conjunction with Henry II’s generally stalwart castellans, their role was in the northern counties after the initial campaign against the invading Scots undertaken by Richard de Lucy and Humphrey de Bohun.

Twelfth-century warfare was not all about soldiers. For sieges, craftsmen and equipment were required, and here too the co-ordination and reach of Henry II’s administration in England was impressive.

The total amounts allowed to Robert and Ranulf for payments made to knights and sergeants amount to £1,228 16s. 10d. and £918 10s. 1d. respectively, monies that would have paid for quite impressive forces.

For the siege of Leicester in 1173, equipment for siege engines was sent from Northamptonshire, 24 carpenters and their master from Staffordshire, arrows and pickaxes from Gloucester, spades and pickaxes from Worcestershire, 41 carpenters and their master from Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, while another 115 carpenters came from Warwickshire and Leicestershire, as well as further equipment.

Also, one of the government’s most striking feats of coordination across a number of localities was in 1173, when the king wished to gather a fleet of ships near Sandwich in Kent ‘ad custodiam maris’. Ships were sent from Colchester, Orford, Dunwich, and perhaps elsewhere in Norfolk and Suffolk, as well as from Lincolnshire and Yorkshire.

If, in part, the suppression of the rebellion was a triumph of the Angevin administration’s capacity for organization – and the pipe rolls reveal just how great that was – in the end we must still return to people and events. The operation of the governmental system depended completely on the loyalty of those who operated it. The sheriffs and others who were separately responsible for other accounts in the rolls were of course vital, but they too depended on the loyalty of those in castle garrisons, or those leading, or participating in, other Pipe Roll 21 Henry II, pp. 7, 173–4.

For the 1173 campaign in the North by the justiciar and constable, see for example Chronica, vol. 2, p. 54; Jordan Fantosme’s Chronicle, pp. 54–63. 59 Pipe Roll 19 Henry II, pp. 33, 58, 156, 163, 173, 178. We also find a mangonel at Berkhamsted: ibid., p. 21. In 1173–74, the sheriffs of Norfolk and Suffolk are credited for the cost of conducting 500 carpenters to the king at Sileham in Suffolk when he was threatening to besiege the Bigod castles. Also, from the farm of Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire, an engineer, Yvo, was paid for hiring carpenters to make machines ‘quando rex venit ad Hunted’ (Huntingdon): Pipe Roll 20 Henry II, pp. 38, 82. It is interesting too that, in the account for Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, although crossbowmen are nowhere mentioned specifically, there is an allowance for the acquisition of 1,000 quarrels (crossbow bolts), though in this case defence of castles is a more likely purpose: ... military forces". ibid., p. 56. 60 - Pipe Roll 19 Henry II, pp. 2, 13, 31, 117, 132–4. 58 (6)

So, from all of this it it clear that a lot of money and resources went into the Castles of Hertfordshire. The use of skilled workers would have been required by both sides in the various conflicts that took place over the two hundred years or so after William swept to power.

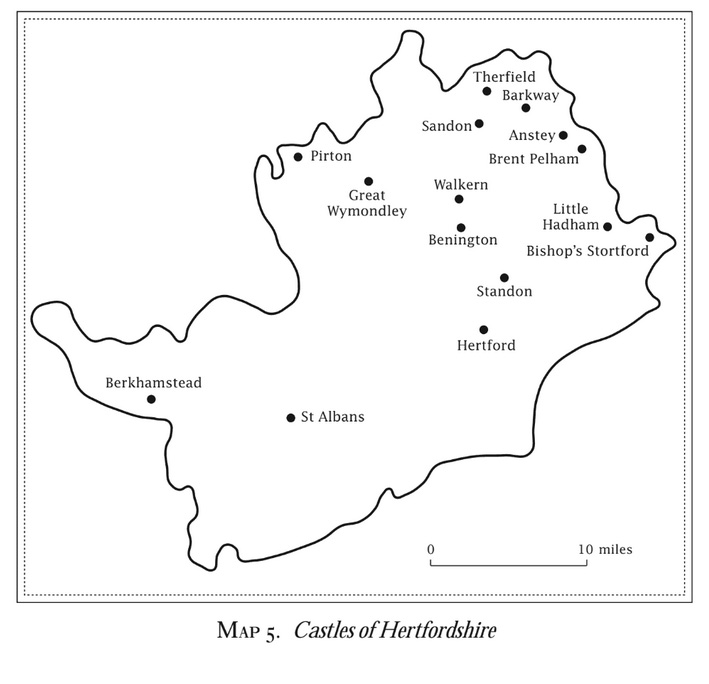

Indeed, some of these castles were built at numerous locations around northeastern Hertfordshire in places where there were a lot of 'Gynns' present nearby: Anstey, Barkway, Therfield, and other locations. Also, Aston and Stevenage are very near Benington. This corelation seems to be more than co-incidental.

The Castles of Hertfordshire (7)

As well, we can't overlook the presence nearby Berkhamsted of Sir John Peryent who showed up along with Edward the Black Prince. (Sir John was granted a manor in Digswell, roughly sixteen miles away.) They must have brought in workers: engineers, craftsmen, stone masons, carpenters, etc to do their work. We already know about the marriage of John Ginn to Mary Gill who was a descendant of Sir John Peryent and it is possible that the relationship between Peryents, Gills and Gynns goes back in time. (For instance the hiring of servants with identical surnames by Peryent and Gynn in 1440, 220 years before John and Mary were married) (8) The family names 'Bohun' and 'Lucy' also seem to figure in this history. There is no known connection, however there may have been other forms of allegiances.

George Gynn came from Stevenage and went to London to become a merchant-tailor. Might his ancestors have practiced as 'Linen-Armourers'? Could this venture have otherwise been spawned from his knowledge of or involvement in wool farming, or trade? Wool was a significant wealth engine in the region around Berkhamsted and Hitchin just as it had been in Lavenham.

Lastly, there is William Ginne in Berkhamsted in 1484. He is shown as an 'innholder' and executor of Richard Kymbell. (CP40/890, Early WAALT findings) About 140 years before this, in 1347, one Robert de Kymbell and his wife, Christiana, had been awarded a very large lease of manors, land and tenements in Berkhamsted directly from Edward, The Black Prince, long before his death in 1376.

It seems that this 'Robert de Kynebell' was a farmer of the manor of Berkhamsted but that his tenure fell into arrears. The date of record is around 1355. The lands held were returned to the prince 'by surrender of the said Robert'. Some of this property had been passed to others by the mid 1350's with a large lease going to a 'Henry Berkhamsted' in 1358. Presumably, descendants of Kymbell still held land in the late 15th century but I don't know where. The real question is what is the connection between William Ginne and Richard Kymbell? (Read backstory)

Note that a transaction between Hugh de Ponytz and a Robert Kynebell was witnessed by a 'William Gysne' in 1355 but it doesn't state where he was from. The likelyhood is that it is either 'Dullyngham' or London.

"Enrolment of release by Hugh de Poyntz, brother of Sir Nicholas de Poyntz, lord of Corymalet, to Robert Kynebell of Berkhampstead and to Christiana his wife of all his right and claim in the manor of Dullyngham, CO. Cambridge, which he had for life of the grant of the said Sir Nicholas, for 101. yearly. Hugh has also made a general release to Robert and Cristiana by this deed". (See note)

A further explanation of the occurrences of the 'Gynn' name seems to be related to subsequent military campaigns of King William I.

The Continuing Conquest, 1067-1072:

"By 1068 a series of uprisings or rebellions in the north were undertaken, in turn, led by Eadgar the Aetheling ... William’s response was resolute with the Conqueror resorting to terror tactics. Late in the year 1069, he fought his way into Northumbria and occupied York, buying off the Danes and devastating the surrounding country in his well-known ‘Harrying of the North’. He spent the winter of 1069-70 laying waste all before him, until all resistance was ended". (9)

The Siege of Exeter (1068)

"The siege of Exeter occurred in 1068 when William I marched a combined army of Normans and Englishmen loyal to the king west to force the submission of Exeter, a stronghold of Anglo-Saxon resistance against Norman rule". (10)

"Exeter had been newly invigorated after the rule of the Saxon Athelstan (928AD)

[William] sent emissaries to Exeter to extract a tribute of £18 per year and force the citizens to swear allegiance to him, but to no avail. The citizens of Exeter sent a deputation to William that stated -

"We will not swear fealty to the King, nor admit him within our wall; but will pay him tribute, according to ancient custom".

A personal appearance was needed for this rebellious city!

William determined to take the city and prepared for a long siege. His engineers dug tunnels under the East Gate and wall to undermine it. After 18 days, the wall partially collapsed and negotiations were held with the citizens within. William persuaded the defenders to surrender after Bishop Leofric and his clergy carried their holy relics and sacred bible from the Cathedral to William, for him to swear a holy oath that he would not harm the city and its people. With that, he sped off to quell the rebellious Cornish.

Gytha, who had been in residence the whole time, escaped by the Water Gate and down the river by boat. Properties were divided among the conquerors, with William becoming the new owner of 285 houses.

Almost immediately, Baldwin Sheriff of Devon was charged with building a castle at Exeter and 48 houses were demolished to make way for it. The gatehouse of the castle was the first to be built and is the earliest Norman structure in the country, with both Norman arches and Saxon windows and stonework in evidence. (11)

The quelling of the resistance was a scorched earth approach and people paid a heavy price for rebelling.

So these other areas where the 'Gynn' (or variant) name is also common, in Yorkshire and in the southwest in Devon and Cornwall, seem to be coincidental with the subsequent conquests of William to suppress rebellions in these areas. This may even include Hereward's last stand, as shown on the above map, in the Fens at Ely. Edward, the Black Prince, was also Earl of Cornwall but his base was at Berkhamsted. Could it be that early 'Gynns' were important people in support of men like William, Edward or John Peryent?

"In the year 1071, though some reinforcements had been received, the skill of William's engineers, improved from experience, by a due combination of causeways and boats, forts and engines, formed a sufficient passage for the troops over the marshes and waters, and after several attempts, the defences were forced, and victory declared in William's favour." (12)

That the derivation of the 'Gynn' name may have been related to the 'gin', or engine, or ingenieur also seems to corelate with the occurrence of 'Gyn' individuals present in places where these men, and also Prince Louis, were involved in warfare as well as castle destruction and rebuilding is definitely interesting. This is all speculation but on the surface at least, early 'Gynn' history seems related to the machinations of these men.

Notes:

1: https://www.stalbanshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/1938_01_BRAUN_with_notice.pdf

2: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berkhamsted_Castle; The de Vere family also figured prominently in the wool trade in Lavenham, Suffolk.

3: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/berkhamsted-castle/history/

4: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berkhamsted

5: https://www.stalbanshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/1938_01_BRAUN_with_notice.pdf

6: https://dokumen.pub/rulership-and-rebellion-in-the-anglo-norman-world-c1066-c1216-essays-in-honour-of-professor-edmund-king-1472413733-9781472413734.html; pg 176 and 177; includes references inline in text.

7: England under the Norman and Angevin Kings: 1075-1225 by Robert Bartlett, Oxford University Press, Aug. 8, 2002; https://books.google.ca/books?id=Ik5yDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA271

8: Found at: England’s Immigrants Database

9: The End of Saxon England? Revisiting the Norman Conquest: Chapter I – The Confessor, the Conqueror & the House of Wessex, 1035-1135; https://anglomagyarmedia.com/2021/08/10/the-end-of-saxon-england-revisiting-the-norman-conquest-chapter-i-the-confessor-the-conqueror-the-house-of-wessex-1035-1135/

10: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Exeter_(1068)

11: Sources - Two Thousand Years in Exeter by W G Hoskins, Exeter Past by Hazel Harvey, The Story of Exeter by A M Shorto and educational notes held in the West Country Studies Library; http://www.exetermemories.co.uk/em/_events/william_siege.php

12: The genealogical history of the Croke family, originally named Le Blount, vol. 1 by Croke, Alexander, Sir, 1758-1842; https://archive.org/details/genealogicalhist01crok/page/96/mode/2up