Flemish Migration to England

Fourteenth Century England – A Place Flemish Rebels Called ‘Home’

In 1354, Lawrence Conync became a freeman of the city of York. Conync was a weaver from the Flemish textile town of Deinze, south of Ghent. As many other immigrants from Flanders had done before him or would do in years to come, he must have acquired the freedom of the city in order to conduct a trade or to work as a craftsman. Unlike most of his fellow Flemings, however, Conync had not left his county voluntarily. Together with his wife, he had been banished in the aftermath of an armed rebellion against the Flemish count during the years preceding his arrival in York.

source: https://www.englandsimmigrants.com/page/individual-studies/fourteenth-century-england-a-place-flemish-rebels-called-home

The Flemish Origins: Descendants of Charlemagne (The Seton Archive)

From: Beryl Platts, The Origins of Heraldry, The Proctor Press, Greenwich, London, UK, 1980.

In the 9th and 10th centuries the comparative stability and prosperity of Flanders caused a number of ancient comtes around her perimeter to attach themselves to the new power. Among them were Hainaut, Mons, Louvian, Alost (or Gand), and Guînes. Boulogne, with it’s own subsidiary comtes of Lens, Hesdin and St. Pol, was also allied to Flanders, as was Ponthieu, away on the Norman border. All were linked by close personal ties to the comital family of the Baldwins. All regarded themselves, and were ruled in 1066 by men directly descended from Charlemagne.

Through Lothair, son of Charlemagne’s third son, Louis the Pious, the counts of Alost trace a connection with the Holy Roman Empire; Guînes was an offshoot of this house via Theodoric, Count of Gand, a younger son of that count of Alost who had married Lieutgarde, daughter of Count Arnulf I of Flanders – himself a ruler who was not only a Charlemagne descendant but had married one in Adela (some genealogists call her Alix), daughter of Count Hubert II of Vermandois, whose own great house descended directly from Pepin, King of Italy, Charlemagne’s second son. The richest Carolingian ancestry of all was that enjoyed by the Count Eustace II of Boulogne; not only did he descend, through Ponthieu and Guînes, from Charlemagne’s favourite daughter, Berthe, and the poet-courtier, Angilbert, who during the emperor's lifetime had been given west Flanders to rule over, but he was also the great-grandson, through his mother, Maud of Louvain, of Charles, Duke of Lorraine, the last male heir of the Carolingians.

... Gilbert of Ghent, another younger son, brother of Baldwin, Lord of Alost, also gained a vast reward, his manors stretching into fourteen counties. Like most of the other Flemish noblemen, Gilbert was a close relative of Eustace of Boulogne, his great-aunt, Adele of Gand, being the Count’s grandmother. (Much more here, article is seven pages)

This document provides an excellent overview of Flemish migration to various parts of England, Scotland and Wales. Included here are extracts which pertain to the very earliest of these migrations ... The influence of the Flemish nobility extended far and wide. As well, a disastrous flood in the 12th century forced many Flemish from their homes and many settled in various parts of The British Isles but particularly Wales.

"Following the Norman Conquest, there came many Flemish weavers who had a large share in the

development of England. Dutch immigrants started sheep-farming, which was to contribute so

much to England's early greatness. The Flemish type of industrial organisation inspired the

formation of the English guilds of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In the twelfth century Dutch

merchants had their own private wharves in London and were members of the Guildhall. At the time

of the Conquest, many Anglo-Saxon refugees settled in the Low Countries. Time and again, Dutch

soldiers have fought on English soil, where some of their descendants now are. In 1165, for

example, Henry II fought the Welsh with Flemish and Brabant troops. " (pg 15)

Note: Text origin : http://pacificcoast.net/~deboo/flemings/pages/Migrations.html is no longer available.

Scotland:

Indeed; delving further into it, it seems the Flemish had quite a disproportionate influence on the British Isles, especially in the

"Celtic" regions. Here is some additional information on settlement in Scotland (as well as the origins of some prominent

clans).

For the Anglo-Flemish, the half century between the Norman Conquest of 1066 and the witnessing of that Glasgow Inquisition

which brought them into Scottish affairs in 1116 must have seemed like the summit of the world. After the awe-inspiring

repulse of the Vikings by their fathers in Flanders, they had gone on in their own time to reach and sustain a pinnacle of

achievement never known before in the history of a nation. Nationhood itself was a very young concept. Family bonds, loyalty

to a liege lord, be he count, duke or king, the honour of a sacred cause, adherence to the chivalry code - these things were

what bound men together, with national borders apt to be secondary to kinship, perhaps because they were so unfixed. Those

Flemings who had followed Count Eustace II of Boulogne to England in 1066 and received their territories there from William of

Normandy, were now being offered large tracts of Scotland because their Lady had become that country's Queen...

Note: Text origin : http://amgl.net/scotland/flemfam.htm is no longer available.

"The nobles of Flanders were required to prove their noble descent through both the

paternal and maternal lines. At Gent, Courtrai, Saint-Omer, Bergues, Bourbourg and Ypres, the

comital and castellan families came from nobles who had held estates and public authority in

these areas since the establishment of the Baldwins as Counts of Flanders. At Veurne, however,

power was held by the Erembalds, who were ministeriales from the Veurne region. The

Erembalds of Veurne who were rewarded for helping Robert I in his conquest of Flanders in

1071. After that, the Erembald's rights as freemen were acknowledged throughout Flanders,

their chiefs were received at court on an equal footing with the nobles, they occupied high

positions in the church and state and their daughters were married to feudal lords. The most

powerful of these Karl families was the House of Erembald. " (section on the Rutherfords, pg 23)

"The Flemish Diaspora in Britain

A genuine "genesis story" for the Clan Rutherfurd by necessity began with a detailed study of

each and every Scottish family that had ever signed a charter, marriage contract, agreement of

manrent or any other document between 1140 and 1498. These families included the de Rydel,

de Percy, de Morville, de Normanville, de Stutteville, de Vaux, de Neufmarche, de Valoniis, de

Lucy, de Lacy, de Insula, de Ghent and, of course, the Douglas family. It has become very clear

that all of these Scottish families had Flemish connections."

""William, Duke of Normandy, needed ships and skilled officers for his invasion of England in 1066. The

Flemish Nobles agreed to lend him 42 ships and crossed the channel themselves to fight with the

Normans at Hastings and were duly rewarded in return for English land grants. Arnulf and many

Flemish nobles fought on the right wing opposite Harold of England and undoubtedly contributed

greatly to the Norman victory. Arnulf received land grants in 14 English counties, including part of

Oxfordshire, where he built Chipping Norton Castle". William the Conqueror was wise to seek the help of the Flemish Nobles as they were the best

educated nobles in Europe, who were great shipbuilders and international traders, experts in science

and agriculture, not to mention their military prowess.

"Arnulf, despite the fact that he was a second son of a second son in his family, was nevertheless an

important figure in Europe; he married a daughter of Ralph de Ghent, Peer of Flanders and Lord of

Alost, and his wife Gisela, daughter of the Count of Luxembourg; and his father. Folk, married a

daughter of the great European family of Vermandois. He was related to most of the Counts in

Flanders and it is said that his pedigree was revered by the Flemish." (pg 38)

"It has not been sufficiently understood that the wars of the Scottish succession were intimately

concerned with an insistence by the Boulonnais there that their own blood should continue on

the throne. For Flemings had married Flemings and by now south and east Scotland was largely

populated by men and women whose ancestors had come from Gent, Guînes, Ardres, Comines,

St Omer, St Pol, Hesdin, Lille, Toumai, Douai, Bethune, Boulogne." (pg 40)

"Investigation into the rise of the European nobility - where they came from, who they were - has

only recently become a subject of interest to continental historians. These 20th-century

researchers have put forward various theories; some of them are in conflict with each other,

chiefly because of regional differences. But the belief that the noble families of the northern part

of the Continent were sprung from marriages of Charlemagne's children with the commanders

of his civil or military' administration, retaining at least some of that power, is substantiated by virtually all the genealogical

documents that have survived those distant times.

The regions where the ruling families were of Carolingian descent embrace the "comtes" north

of the Ile de France, east of Normandy, west of Germany, including of course the whole of

Flanders - a description here used broadly to include territories like Brabant and Hainaut which,

though theoretically independent, were in practice part of the political ambience of the Flemish

counts, and for long periods under their direct control. (pg 41)

"LINDSAY:

Baldwin of Alost and his younger brother, Gilbert de Ghent, companion of the Conqueror, were

sons of Ralph of Alost and cadets of Guînes. Gilbert de Ghent, Earl of Lincoln, was father of

Walter de Lindsay, ancestor of the Scottish family of Lindsay" (pg 46)

"The Flemings in South-West Wales:

The deliberate introduction of Flemish settlers to south-west Wales by King Henry I was to

transform the landscape and culture of the region.

The Flemings were to become a thriving and distinctive community, retaining their own language

and racial identity for more than a century.

In the 1180s, the scholar-cleric Gerald of Wales (d.1223) described the settlers of his native

Pembrokeshire as 'strong and hardy people... a people who spared no labour and feared no

danger by sea or by land in their search for profit; a people as well fitted to follow the plough as to

wield the sword'.

It was the Norman flair for economic reorganization which led them to introduce Flemish settlers to

occupy newly-conquered territories and areas of waste land. Such a process of deliberate

colonization and manorial settlement was to underpin every stage of their military success. The

Normans were by no means unique in this respect; it was the approach also adopted, for

example, by the counts of Champagne and Flanders. Driven from their homeland by incursions of

the sea and by overpopulation, the Flemings migrated far in search of new lands and economic

fortune. They may well have played a significant part in the Norman colonization of Ireland, and

they settled extensively in northern England and parts of Scotland. They also moved east from

their homeland, traveling beyond the river Elbe in Germany to settle the native forests of central

Europe. " (pg 48)

"The Settlement of Low Dutch in England, and General Intercourse

In the Middle English period the Low Dutch people which had the most intercourse with English

was naturally enough the Flemish. Most of the Flemings who came over with William I were

soldiers, and these did not all return to the Continent when the Conquest was completed. Some

were planted out at special points as military colonies, as, for example, that under Gherbord at

Chester. This policy was continued by William II, who established a military colony at Carlisle.

William I replaced the higher native English clergy by foreigners, and Flemings had their share in

the appointments, e.g. Hereman, Bishop of Salisbury, Giso of St. Trudo, Bishop of Wells, Walter,

Bishop of Hereford, and Geoffrey of Louvain, Bishop of Bath.

Thierry states that not only soldiers, ecclesiastics, and traders, but whole families came over.

Matilda, William's queen, was the daughter of Count Baldwin V of Flanders, and doubtless she

had many Flemings in her train.

The immigration of Flemings went on steadily after the Conquest and in such numbers that Henry

I did not know what to do with them. There is a tradition that in his reign an incursion of the sea

made thousands homeless in the Low Countries and that the refugees came to England. They

were settled first on the Tweed, but four years later were transferred to Wales. These settlements

were reinforced in 11 05 and 1 106, and according to Florence of Worcester Henry sent another

large body to South Wales in 1111. The colonies at Haverfordwest, Tenby, Gower, and Ross may

have been intended to keep the Welsh in check; at any rate that was the result, for the districts

settled lost entirely their Welsh character, and the dialects spoken in them to-day retain in

vocabulary a pronounced Flemish element. Some of the Flemish mercenaries who came in

Stephen's time were deported to Wales. " (pg 50)

This key document also includes the following:

Flemish Counts Of Guînes

Gilbert de Ghent was also known as: Gilbert "de Gand" (Lord Folkingham) Billungen and Gislebert dit “Le Grand” van Gent, baron de Folkingham, seigneur de Hunmanby

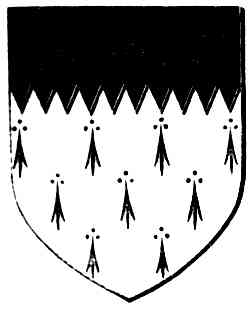

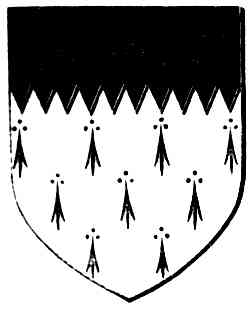

But this person presents with different arms.

Other spellings of the name include 'Gaunt', 'Ganz' and 'Ganda'.

See also: Gilbert Gent (died 1095)

Flanders

The great Charlemagne provided the northern part of Europe with its nobility. Charlemagne's children married

his civil and military administrators. Those families retained some of that responsibility and power into future

generations, giving a structure to the society of those distant times.

The Carolingian families were found in the comtes north of the He de France, east of Normandy, and west of

Germany. The Carolingians were also found in Flanders. At this time, Flanders included territories like Brabant

and Hainaut which, though theoretically independent, were in practice part of the political ambience of the

Flemish counts, and for long periods under their direct control.

Flemish law forbade noble men and women to marry outside their own class. Many Carolingian families

married distant cousins and the like. This law followed the Flemish nobility wherever they were. Its effects

were especially apparent in Scotland where all the non-Celtic aristocracy were related.

The descendants of the Counts of Flanders followed two lines. The primary line, the descendants of the Counts

of Flanders, arrived in England in the person of Matilda of Flanders (granddaughter of Count Baldwin IV of

Flanders and Ogive of Luxembourg), wife to William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy.

The secondary line, the descendants of the Lords of Alost, arrived in England when the sons of Ralph, Lord of

Alost and Gisela of Luxembourg (Ogive's sister) accompanied William, Duke of Normandy.

The Counts of Alost

Count Arnulf of Flanders made a pact with Emperor Otto I, persuading Otto to retire from Ghent during the

10" century. The defence of Ghent became the responsibility of Flanders.

A new comte called Alost was formed as a buffer between Flanders and the Lorraine border. Alost was given

to Arnulf s nephew, Ralph (son of his brother Ethelwulf, who had acquired his name from a Saxon mother —

Elstrudis, King Alfred's daughter). Ralph died in 962.

Under the Flemish regime every man who ruled a comte had his device, unique to himself and his land. The

device passed with the inheritance to his heir at the moment of succession.

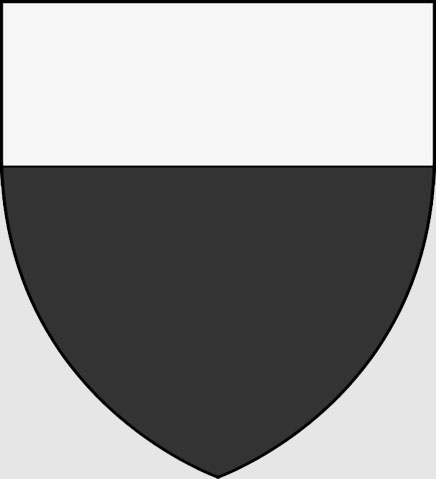

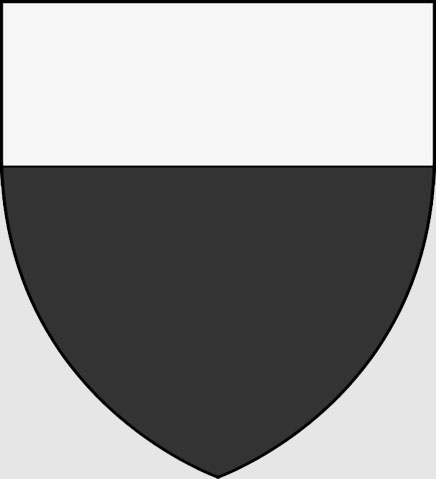

The Counts of Alost bore sable, a chief argent. The black and silver tones, which these words denote, came to be

understood as the colours marking the region around Ghent.

Ralph's son, Baldwin succeeded him as Count of Alost. Baldwin was a vassal of the Emperor, a duty that

would continue for several generations. It was not an unusual arrangement; many Flemish counts held more

than one allegiance.

The Lords of Alost were among the first six peers created when the peerage of Flanders was formed in the

middle of the 11" century. They had a known descent by at least three lines from Charlemagne and were

regarded as the noblest of the nobilitas.

The comte was held by Ralph, Lord of Alost, between 1031 AD and 1052 AD. Ralph married Gisela, daughter

of tlie Count of Luxembourg (whose sister Ogive was married to Count Baldwin IV of Flanders). Ralph's

children were first cousins to William tlie Conqueror's wife, Matilda of Flanders.

Ralph and Gisela are known to have had at least four sons and several daughters. The known sons were:

• Baldwin I, the heir to Alost

• Ralph II, who became Chamberlain to the Count of Flanders

• Gilbert, who accompanied William the Conqueror to England and received land in 14 counties as his

Domesday reward, and

• Ragenfridus.

Baldwin I of Alost was likely to have accompanied William the Conqueror to England in 1066 AD. He would

have brought a substantial army of his own men, and men of Brabant. Baldwin I died in 1082 AD, too early for

Domesday rewards.

Baldwin II of Alost (sometimes called the Fat") was killed in Nicaea in 1097 AD while following his leader and

kinsman, Godfrey de Bouillon, on the First Crusade. Albert of Aix noted that Baldwin was "carried away by his

ardour and the wish to reach the walls, had his head pierced by an arrow and died in combat" during the assault

on Nicaea.

Baldwin III of Alost died in 1127 AD from the effects of a head wound received during the struggles for the

Flemish comital succession. He left no legitimate male heirs, and the heritage, which should have passed to his

daughter, Beatrice, was annexed by the family's black sheep, Ivan, who succeeded him as Lord of Alost.

The seizure of Beatrice's patrimony caused a feud between other members of the family and their senior branch,

the Counts of Guînes, which was to last for many years and lead to Ivan's murder. Ivan's only son, Thierry

(sometimes called Dirk), who married the daughter of the Count of Hainaut, brought some sort of natural

retribution to the situation by dying in 1166 AD without heirs.

The county, its revenues and its titles were withdrawn into the treasury of the Counts of Flanders. However,

the arms of the comte, a black shield with a silver chief (a broad band running along the top) were taken by a

cadet branch of the house who had been castellans of Ghent and Advocates of the abbey church of St. Peter at

Ghent since the 9th century.

The Norman Conquest

Ralf de Limesi was bom in Alost about 1040 AD. He had a small Norman manor in Limesi, on the north side

of the Seine valley. He was the Chamberlain, to the Flemish Court. Ralph de Limesi left a son, Alan, in

Warwickshire and heirs of unknown name in Limesi.

Ralph de Limesi (or Ralph de Ghent or Ralph de Lindsay) came to England with William the Conqueror in

1066 AD. He received Domesday estates in Somerset, Devonshire, Hertfordshire, Northamptonshire,

Warwickshire (his most important holdings), Nottinghamshire, Essex, Norfolk and Bedingfield, Suffolk as

tenant in chief.

Ralph's coat of arms was gules, an eagle displayed or.

Ralph de Limesi and his wife, Hawisa, founded Hertford Priory and they were generous benefactors to the

Priory thereafter. Ralph died in mid-1090's in the monastery of St Albans.

Alan de Limesi built a church dedicated to St Andrew at Collyweston in Nortliamptonshire.

Aleonora de Limesi, Ralph's great-granddaughter and heiress married Sir David de Lindsay of Crawford a

distant relation. Her sister, Basilia de Limesi, married the Flemish knight. Sir Hugh de Odingsels.

Gilbert de Ghent (de Lindsay), son of Ralph, Lord of Alost, married Alice de Montfort sur Risle, a distant

relative.

^\maury de Valenciennes, Count of Valenciennes, was in conflict with the Count of Flanders during tlie first

decade of the 11* century. Amaury de Valenciennes fled to France where he became the first Amaury de

Montfort. Valenciennes was seized by Flanders during the conflict. This effectively removed the comte from

Hainaut control and was a source of contention for some time.

Hainaut's Countess Richelde married Baldwin of Mons (afterwards Baldwin VI of Flanders) a few years before

the Norman Conquest of England. This ended the contention about Valenciennes between Hainaut and

Flanders. The marriage of Gilbert (cousin to the Count of Flanders) and Alice (descendant of Amaury de

Montfort) also had a healing diplomatic significance.

Knights such as Ralph de Limesi had probably received their lands from the Alontforts at the time of Gilbert

and Alice's marriage as part of tlie general reconciliation. Hainaut had ruled Alost itself before the Flemish

seizure of Valenciennes.

Gilbert de Ghent accompanied William, Duke of Normandy, on his expedition to England. Gilbert took an

active part in the subjugation of England: the city of York was placed under his command in 1068 AD, together

with William Malet. In 1069 AD, an invading force captured tlie city, killed the Norman garrison and only

spared Gilbert and William for their ransom.

Gilbert de Ghent brought the Alost colours (sable, a chief argent) to England in 1066 AD, and he may have had

them carried in front of his own troops there. The family devices were an important part of their Flemish

culture and provided a strong sense of identity in a new country.

An adaptation of the Alost coat-of-arms was used in the great priory at Bridlington, Yorkshire: per pale, sable and

argent with the unusual addition of three Bs for Bridlington.

He received 172 English manors; most of them in Lincolnshire (Gilbert was the first Earl of Lincoln) and

Nottinghamshire, through the shires of York, Derby, Huntingdon, Leicester and Cambridge also provided

extensive estates.

Gilbert and Alice made their chief home at Folkingham, near Grantham. Their children include (there were

others, unnamed by chroniclers) :

• Gilbert II , Hugh , Walter I , Robert I , Ralph III , Henry , Emma and Agnes

Gilbert died in 1095 AD. (There are many more stories about Gilbert's activities after the Conquest.

Unfortunately, we do not have the space to include them in this article. - Ed)

(See also: Family of Vilain XIIII: Wikipedia and Vilain (Arms and Heraldry)

Gilbert de Ghent II was not well known. He may have been a victim of ill health or he may have spent most

of his time in Flanders, helping to hold the comte of Alost for his family during the First Crusade and the

troubled years, which followed the death in that campaign of his cousin, Baldwin II. He left no heirs.

Hugh de Ghent, Gilbert's second son, inherited the Norman lands of Montfort-sur-Risle from his mother. He

became Hugh IV of AIontfort-sur-Risle. Hugh married Adeline de Beaumont.

Walter de Ghent (or de Lindsay), Gilbert de Ghent's third son, was married twice. His first wife is virtually

unknown; his second wife was Maud of Brittany. Walter accompanied David, Earl of Huntingdon, brother of

Alexander I, to Scotland to claim his throne. Walter de Lindsay settled at Tweedside, from Earlston to

Caddonlea.

Walter de Lindsay had two sons by his first wife: Walter II and William

Walter de Lindsay was a witness to the very important Inquisitio into the See of Glasgow, around 1116 AD.

Other witnesses include Matilda the Countess, Count David's nephew, William, Osbert de Arden (a

Warwickshire man who lived near Ralph de Limesi) and Alan de Percy, husband of Emma de Ghent (Walter's

sister).

Count David (future king of Scotland) signed a charter in 1120 AD, founding tlie Abbey of Selkirk. The

signature of Galterio de Lyndeseia (Walter de Lindsay) also appears on the Charter — the first to be found in

Scotland of the great name of Lindsay.

Walter de Ghent inherited the Lincolnshire estates late in life and somewhat unexpectedly. Walter married

Maud of Brittany around 1 120 AD. They had three sons: Gilbert III- a minor when his father died ,

Robert and Geoffrey

Walter and Maud lived at Bridlington, Yorkshire.

During the civil war (1135 AD to 1152 AD) Walter supported Stephen, whose wife, Matilda, Countess of

Boulogne, was his kinswoman (Gilbert de Ghent's great-aunt, Adele, married the father of Count Eustace I of

Boulogne). Walter participated in the Battle of the Standard. He supported the very moving appeal made by

Robert de Bruce to David, King of Scotland, "not to bring war between men who were kinsmen and

comrades". Bruce had a son on the opposing (Scottish) side, and so did Walter de Ghent — for Walter de

Lindsay II was by now established with his family at Ercildon.

Walter de Ghent died 1139 AD.

The Scottish estates passed to Walter de Lindsay II, who was by then married to a kinswoman of the Scottish

Queen.

The children of Walter de Ghent's marriage to Alaud of Brittany enjoyed the English estates without conflict of

allegiance. The possession of the Lincolnshire parishes of Fordington and Ulseby by Sir William Lindsay of

Lamberton at the start of the 13 ' century shows that at least some of the Ghent heritage passed to tlie Lindsays

of Molesworth, who were also the Lindsays of Ercildon.

England

Gilbert de Ghent III, Lord of Lindsay, Earl of Lincoln (son of Walter de Ghent and Maud of Brittany), was

bom in 1120 AD and died in 1156 AD. He married Rohese de Clare. His daughter, Alice de Ghent, married

Simon de Senlis III, a grandson of Queen Alaud of Scotland, and a distant relative.

Gilbert de Ghent VI, of Folkingham (no longer calling himself Earl of Lincoln) died without male heirs in

1297 AD. Gilbert married Lora de Baliol, a kinswoman of King John Baliol.

Robert de Ghent I (son of Gilbert de Ghent and Alice de Montfort sur Risle) was Chancellor to King Stephen.

He died m 1153.\D.

Robert de Ghent II (son of Walter de Ghent and Maud of Brittany) married twice. His first wife was Alice, his

second, Gunmor. He had one son, Gilbert de Ghent IV, who was a minor when Robert died.

Ralph de Ghent III (son of Gilbert de Ghent and Alice de Montfort sur Risle) married Ethelreda, the

granddaughter of Gospatrick, Earl of Northumberland. It is not known if Ralph had any immediate heirs;

descendants of the great Gospatrick all took Saxon or Scandinavian names. William de Lindsay of Scotland

eventually claimed the estates.

Ragenfridus de Lindsay (youngest son of Ralf, Lord of Alost and Gisela of Luxembourg) appears to have

accompanied Gilbert to England. He may also have been known as Angodus de Lindsay. Angodus de Lindsay

may have left sons, but tliey would have been called by the name of his chief manor, which is unknown to us. (pp 15-20)

source: Moutray’s Blog: Moutray / Moultray / Moultrie related Genealogy Research

See original article which includes permissions and sources: Flemish Counts Of Guînes

Vilain and Vilain XIIII (Vilain-Quatorze, sometimes written Vilain XIV) is a Belgian noble family.

OR

OR

Their coat of arms is basically "sable, au chef d'argent" (left) , a colour scheme that is present from the earliest Vilains in the 15th century, and is also seen in the Vilain XIIII arms, which have the "XIIII" added to it.

They were descendants of the important medieval family of Vilain in Ghent; the name "Vilain XIIII" probably comes from the coat of arms of Philippe de Liedekercke, chamberlain of emperor Charles V, who had 16 quarters in his coat, the fourteenth (bottom row, second from the left) of which was the coat of Vilain.

The three main branches of the family were the Princes of Issenghien (the De gand, dite Vilain branch), the Counts of Aalst (the Vilain XIIII branch), and the Counts of Guînes (originally also De Gand dite Vilain, later Vander Steene).

One branch lived at the Chateau of Leuth (or Leut) from 1822 until 1922, when the last of 7 daughters of Viscount Charles Vilain XIIII died. The oldest mentions of "Villain XIIII" date back to the 16th century, but its origin is unknown. Politically, they were usually part of either the Catholic parties, or the Liberal parties. The first known generations were politicians (often bailiff or mayor) in Geraardsbergen and Aalst; the family also owned the county of Wetteren until 1796, and the city coat of arms still bears the XIIII of the family.

House of Gand; Castellans of Ghent; Counts of Guînes

Pertains to:

Boudewijn II van Guînes, comte de Guînes; Rudolph van Aalst; Boudewijn I van Gent; heer van Aalst; Hugues de Montfort, IV; Walter van Gent, lord of Folkingham (aka Walter de Lindsey); Robert de Gant, Lord Chancellor of England, Dean of York; Ethama de Maule (de Vaux); Gilbert II de Gant; Henry de Gant, Emma de Gant; NN (Felia?) van Gent; Ralph de Gent; NN daughter van Gent

House of Gand original blazon;

Issued from Adalbert de Gand, son of Arnulf, Count of Holland

(Uploaded on: October 26, 2020 at 7:20 PM, From the album Belgium, Flanders & Netherlands CoA by Private User May 9, 2021 at 1:04 PM)

(design by JSpeuller at Wappenwiki.org, licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), resizing and tincture variations by dbigelow)

A similar arms appears on The Heralds' Roll: 378 Chastelain de Gant

Sable a chief argent

Hugh IV de Ghent, who also appears in The Camden Roll, D267 as well as: 392 Sir Sansch

Sable on a chief argent a fleur de lis issuant gules

Ghent, who also appears in The Camden Roll, D226 and;

393 Ernold le Diable

Sable on a chief argent a a lion passant gules

Gerard le Diable de Ghent

These men are all from Ghent.

A similar motif is used by the commune of Houplines

Thursday, April 15, 2021

A Final Post from St. Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium by David B. Appleton

This final post about heraldry in St. Bavo's Cathedral, and indeed the final post from Ghent and from Belgium, is a bit of potpourri of heraldry.

Note: Halewyn, Argent three lions rampant sable;

Vilein, Sable a chief argent.

"Guant" - Additional names given by Duchesne

Few among the Conqueror's companions of arms were so splendidly rewarded as Gilbert de Gand, who held one hundred and seventy-two English manors; yet there is much doubt—or at least much difference of opinion—as to who he really was. (Transcribed by Michael Linton)

This, of course, raises questions about what Gilbert de Gand did to be the benefactor of such generosity. It also raises questions about how his family spread throughout the Kingdom, for example where second or subsequent sons (and also daughters) were concerned, what happened to them?

" It is in the many very different flags that evidence of inchoate heraldry may be discerned, and, although the illustrations were executed by ladies uninformed of heraldic convention, the flags have sufficient detail as to suggest the identity of Boulogne (or three torteaux) and Alost (sable a chief argent) among other Flemish nobles. The Counts of Alost and Boulogne were among the best-rewarded when William shared out England among his army’s leaders, so one would expect the tapestry to recognize the value of their contribution by identifying them with their flags. (The Count of Boulogne appears also, with a flag bearing the arms his sons would later fly above Jerusalem.)" Heraldry, Encyclopedia Britannica by Leslie Gilbert Pine and Frederick Hogarth.

Gand/Ghent

Counts of Flanders

Flanders (Flemish) Nobility

Houplines is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Blason de la ville de Houplines (59) Nord-France, described as: "De sable au chef d'argent."

(Ennetières-en-Weppes, Houplines and Sailly-lez-Lannoy use the same arms.)

This is the same as: "The Counts of Alost bore sable, a chief argent. The black and silver tones, which these words denote, came to be

understood as the colours marking the region around Ghent". (see: Flemish Counts Of Guînes, The Flemings - Flemish migrations and influence by Jaime Lavid, 2011 - issuu in 'Flemish Migration to England' article.

Similar arms are used by Ennetières-en-Weppes and Sailly-lez-Lannoy which are communes in the Nord-France (59) region.

See also: The Noble and Gentle Men of England, by Evelyn Philip Shirley (Project Gutenberg)

"Gentle: Gent of Moyns.

The family of Gent was seated at Wymbish in this county in 1328. William Gent, living in 1468, married Joan, daughter and heir of William Moyne of Moyne or Moyns. His widow purchased that manor in 1494, and it has since continued the seat of this family, who were greatly advanced by Sir Thomas Gent, the Judge, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

See Morant's History of Essex, ii. 353.

Arms [described as:] Ermine, a chief indented sable. Sometimes a chevron sable is borne on the field. The Judge bore two spread eagles on the chief, as appears by his seal.

Present Representative, George Gent, Esq.

Migrations of Flemish Textile Workers

For a variety of reasons, Flemings have been leaving their homeland for centuries: For example, about one-third of William the Conqueror's army invading England (1066) were Flemish mercenaries. (De Bootje Gazette, Issue No. 5, October 2003) (https://web.archive.org/web/20090105224103/http://www.pacificcoast.net/~deboo/belgium.html)

"Perhaps the most notable Flemish fact to that time was that about one-third of the invading Norman army of 1066 came from Flanders (Murray 1985). The Flemish mercenaries were there as a result of a marriage arrangement by William the Conqueror for a niece and a Flemish count. Many Flemings stayed in England after the Conquest.

One of the most enduring Flemish facts in England is related to the immigration of skilled Flemish weavers and textile workers to major centres such as London, Norwich and Colchester from the 11th to the 16th C. Often called 'Dutch' because of language spoken, these Flemings introduced superior sheep-farming methods for the wool trade, and they helped organize and establish the English guild system using the Flemish model".

(Flemish Migrations @ https://web.archive.org/web/20170129223135/http://pages.pacificcoast.net/~deboo/flemings/pages/Migrations.html)

The Flemish colonists in Wales

One of the first arrivals of the Flemish to the British Isles was at the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066. In the 11th Century, Flanders was becoming perilously overpopulated and the Flemish, in the area now known as Belgium, were forced to move. Many moved to Germany, while others joined the Norman army, becoming an important element in their forces. The Norman kings rewarded those who fought with land in the conquered countries, giving them territory to live on, on the proviso that they defended it on behalf on the Norman invaders.

Before the Norman Invasion, Wales was subject to much infighting and was in no position to defend itself with a united front. William I installed his earls along the Welsh border at Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford, and they soon made progress into Wales. The Earl of Shrewsbury took his forces southwest, through Powys and Ceredigion, to Dyfed, where they established a castle at Pembroke.

On the Flemings

‘The inhabitants of this province derived their origin from Flanders, and were sent by King Henry I to inhabit these districts; a people brave and robust, ever most hostile to the Welsh; a people, I say, well versed in commerce and woollen manufactories; a people anxious to seek gain by sea or land, in defiance of fatigue and danger; a hardy race, equally fitted for the plough or the sword; a people brave and happy’. (Geraldus Cambrensis, Itinerary Through Wales, 1188)

Asylum Seekers

Flanders suffered greatly after a series of storms, in 1106. Samuel Lewis wrote, "During a tremendous storm on the coast of Flanders, the sand hills and embankments were in many places carried away, and the sea inundated a large tract of country."

This led a large number of Flemings to seek asylum in England, where they were welcomed by Henry I. They settled in various colonies across England, but soon, Samuel Lewis wrote, they "became odious to the native population", and Henry I moved the Flemings to the remote farming settlement in the cantref, a district of Rhôs, in south Pembrokeshire.

This systematic planting of Flemish settlers by Henry I, and later Henry II, had significant consequences for the people of south Pembrokeshire. Geography Professor, Harold Carter looks at the effects, "If you look at the 'Brut y Tywysogyon' - the Chronicle of the Welsh Princes - it records 'a certain folk of strange origins and customs occupy the whole cantref of Rhôs the estuary of the river Cleddau, and drove away all the inhabitants of the land'. In a way you could almost call it a process of ethnic cleansing."

The influx of Flemings into south Pembrokeshire was so great that the Welsh language was eradicated and Flemish gradually gave way to English as the dominant language. However, it was a dialect spoken with a strong and distinctive accent and with a large vocabulary of words not commonly found elsewhere. (https://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/immig_emig/wales/w_sw/)

Flemish immigrants

Last updated: 15 August 2008

Back in the 12th century, Flanders - a region of Belgium - had been devastated by floods and was becoming dangerously overpopulated. Many Flemish people, or Flemings, escaped to England. Initially welcomed, they soon began to irritate their hosts.

Henry I's solution to what he saw as a little local difficulty was to shift them en masse to a remote farming settlement in south Pembrokeshire.

It was a move that created a divide in Pembrokeshire that exists to this day, between the native Welsh and the incoming Flemish/English. The legacy of 12th century Flemish incomers is 'Little England beyond Wales'.

Castles were built - the Landsker Line stretched from Newgale to Amroth. The Chronicle of the Welsh Princes records "a certain folk of strange origins and customs occupy the whole cantref of Rhôs and the estuary of the river Cleddau, and drove away all the inhabitants of the land". It was almost ethnic cleansing.

The influx of Flemings was so great that the Welsh language was eradicated south of the divide. Flemish gradually gave way to English but with a distinctive dialect and accent - traces of which can still be heard today.

The region has kept its anglicised culture and sense of separation ever since. Until the 19th century it was the only English-speaking area of Wales away from the English border. (https://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/history/sites/themes/society/migration_flanders.shtml)

The Flemish Settlement in Wales

Since the accession of William I many Flemings had settled in England. They did not get on well with the English, and so Henry I moved them to South Pembroke, where they would be useful in helping to keep the Welsh in check. This is of course the beginning of 'Little England beyond Wales'. It is probable that the English speaking people on the south side of the Gower Peninsula were settled there about the same time and for the same reason.

(True also of Kidwelly as it's first Charter has been dated to be at the latest 1114.) W.J.M.

1107

Brut y Tywysogion

A CERTAIN nation, not recognized in respect of origin and manners, and unknown as to where it had been concealed in the island for a number of years, was sent by King Henry into the country of Dyved. And that nation seized the whole cantred of Rhos, near the efflux of the river called Cleddyw, having driven off the people completely. That nation, as it is said, came from Flanders, the country which is situated nearest to the sea of the Britons, the whole region having been reduced to disorder, and bearing no produce, owing to the sand cast into the land by the sea. At last, when they could get no space to inhabit, as the sea had poured over the maritime land, and the mountains were full of people . . . so that nation craved of King Henry and besought him to assign a place where they might dwell. And then they were sent into Rhos, expelling from thence the proprietary inhabitants, who thus lost their own country and place from that time 'til the present day.

Giraldus Cambrensis, Itinerary, Book I, Chapter II

The inhabitants of this province who derived their origin from Flanders were sent to live in these parts by Henry I, King of the English; they are a people brave and robust, and ever most hostile to the Welsh with whom they wage war; a people, I say, most skilled in commerce and woollen manufactures; a people eager to seek gain by land or sea in spite of difficulty or danger; a hardy race equally ready for the plough or the sword; a people happy and brave if Wales, as it should be, had been dear to the heart of its kings, and not so often experienced the vindictive resentment and ill treatment of its rulers.

Extracted from “A Source-Book of Welsh History”, p.67-68 by Mary Salmon, M.A., Oxford Univ. Press 1927. (found at: http://www.kidwellyhistory.co.uk/Articles/Flemish.htm)

Plenty more here: http://www.kidwellyhistory.co.uk/contents.htm

The Flemings of Pembrokeshire

Amy Eberlin, Saturday 2 May 2015

As noted in earlier blog postings (see especially posting dated November 21, 2014) some of the Flemings that came to Scotland had, according to historical records, done so after a period of time spent in Wales. This blog posting by Pamela Hunt examines why the Flemings had come to Wales and describes an ambitious project that seeks to restore an old Flemish church and gain a better understanding of the Flemish footprint in Pembrokeshire.

William of Normandy’s marriage to Matilda, Princess of Flanders, meant that the Flemish became allies to the Normans and indeed Flemish nobles joined the 1066 expedition to invade England. With the success of the invasion some Flemish knights were given land and estates in England. When Henry I became king in 1100 he perceived a troubling superfluity of Flemings (probably disbanded mercenaries and others)

So with one stroke Henry solved two problems. He sent the Flemings to Pembrokeshire

with promises of land there. But more importantly they could help to keep order.

As William of Malmesbury attests, the Welsh were constantly rebelling. It is

believed that as many as 2,500 Flemings were sent to Pembrokeshire.

But this wasn’t the only migration to Pembrokeshire during Henry’s reign,

it seems there was another. According to the Welsh Chronicle of the Princes,

or the ‘Brut y Tywysogion’ written around 1350, it refers to ‘An inundation

across the sea of the Britons, flooding vast areas of Flanders wetlands’.

It goes on to suggest that this was a reason for there being Flemings in

Pembrokeshire. But it doesn’t tell us when during Henry’s reign this happened.

Professor Tim Soens of the University of Antwerp specialises in the history

of Flanders Hydrography and he confirmed that there was a massive storm surge

in October 1134 causing dozens of Wetland villages to be washed away and

thousands killed. Was it out of kindness or a determination to reinforce

his hold on South Pembrokeshire that Henry chose to invite the survivors

of that catastrophe to settle in Pembrokeshire?

source: https://flemish.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2015/05/02/the-flemings-of-pembrokeshire/

OR

OR