"When it comes to Celtic history, separating reality from myth is not easy. The origins, cultural traditions, and historical evolution of the European peoples we now call Celts are all highly obscure. We don't know precisely where Celts came from, nor how they integrated with the indigenous cultures they encountered. (Their relationship with the Scottish Picts, for instance, is quite obscure.) There appears to be no clear or continuous archeological record of Celtic migration or occupation, and little consensus between scholars concerning Celtic genetics and language". (Celtic Culture: Characteristics of Celts Visual Art, Language, Religion.)

Investigations about Celtic cultures are being revisited at an alarmingly rapid pace. This new knowledge is exciting, compelling and also challenges many long-held beliefs about Celts and Celtic culture, starting from ancient times. Theories that have been almost unshakeable since the early 18th century, as proposed by Edward Lhuyd, are now being overtaken but we're dealing with a scant knowledge of things rarely written down and for which the archeological record may only offer tangential evidence.

Celtic culture has deep roots in central Europe, starting from prehistoric times. This culture emanated from a source and spread much further and wider than the Celtic cultures that we know today. Influences from other cultures no doubt merged with Celtic cultures to produce hybrids of expression that manifest in Middle Eastern and even North African modes that are still extant today. As one listens to the music from these quite different regions, one is struck by the similarities in the music, so, why are there these similarities?

"What are the origins of Celtic music? Listening to Arabic and Middle Eastern music one finds many common characteristics similar to the traditional music of Scotland and Ireland. In both cases there is a strong emphasis on the melody and the rhythm, indeed it can be asserted that between the peculiar characteristics of these musical forms the melodic-rhythmic complexity has the main role. Instead we will find very seldom important elements of "western" music, such as harmony and counterpoint." (Celtic music: Introduction by Alfredo de Pietra )

One hypothesis might be that Celtic musical origins began in central Europe in areas like Halstatt and the Pontic-Caspian steppe and slowly dispersed. The mechanism for this might have been traders or merchants, bringing musicians with them from their own homes, for their own enjoyment - and sharing this music, dance, social interactions and so on which resulted in the Celtic styles, instruments and expressions spreading throughout the European continent into Asia-minor and the Middle east and even as far as China and India.

"The ancient Celts had a distinct culture, which is shown by their very sophisticated art work. The Hallstatt culture and especially the later La Tène culture are characterized by a high aesthetic level, which must have also left traces in ancient Celtic music. Music was surely an integral part of this old cross-European culture, but with only very few exceptions its characteristics have been lost to us". (Ancient Celtic music - Citizendium)

Eventually, the musical styles disappeared in many areas. The Romans pushed many peoples from their familiar settlements, or subsumed them. As these settlements waned, so did the cultures they possessed. What we see today is the evolution and continuance of these musical influences in mainly two distinct regions, the modern Celtic and the Middle East where these apparently similar musical styles are still extant. Notably, these are regions where the Romans had little influence.

It may be easy to pass this off as coincidental, however it is important to take the way of looking at this back in time, to a time when current political divisiveness was not a factor and when the exchange of ideas took place on the ground and at the speed of human-to-human contact. Consider that "Music was so important to the ancient Celts that a group evolved called the Bards. Bards were wandering singers, storytellers and poets. A scornful Bard could destroy your reputation with a single song". (History of Celtic Music) "Bardism evolved out of the ancient tradition of fireside storytelling". (A brief history of Bardism - Gorsedh Ynys Witrin) "[I]n all Celtic societies in fact–the bard/poet played a very important role in the life of society. ... but ... The Celtic oral tradition, as it is generally referred to, was forbidden to be written down". (Journey to Medieval Wales ... Sarah Woodbury) For this reason alone, unlike the Romans and the Greeks, much of the record of Celtic peoples has simply vanished.

Celtic music and linguistic styles do not appear to centre on any particular cultural group or race. Rather, these appear to be adopted, shared and disseminated widely/broadly among cultural and linguistic groups. It was as powerful then as it is today. Nowadays, we hear these musical expressions in countries as varied as Australia, Canada, United States, Scotland, Ireland, Spain, Italy and France as well as most Middle Eastern countries; this is a natural evolution of the history that is Celtic music.

Traditional history states that conquest by the Romans forced local peoples away from central and southern regions in England and into Cornwall, Scotland and Wales, or also may have assimilated them. And, the Romans had a similar impact in the eastern part of the Mediterranean, forcing out Celtic influences and pushing them still further east. The Romans never established their influence in Ireland. Later on, the British Isles; England and Scotland, and also Ireland and Wales to some extent, were invaded, occupied and ransacked by northern Europeans: Vikings, Angles, Saxons and so on after about the 7th century.

Sea routes are central to these migrations into the Isles - that is the only way to get to them. However, sea routes from other areas are also known to exist. Less is known about the exchange of people, goods and ideas from these regions - Spain, the Mediterranean and further east. There is little doubt that these exchanges happened but when and where are not well understood.

Land migrations were also taking place. So, peoples moved around, traded goods and ideas, shared, warred, interbred; cultures were born and died out. But ideas become constants that persist through time, are passed on, synthesized, merged in and evolved.

Linguistic similarities point us to connections that are difficult to ignore. The musical instruments, musical phrases, styles and so on are equally difficult to ignore. Again, when we listen to modern interpretations it is clear that connections are indeed present.

Indeed, historical accounts and legendary portrayals contain numerous references to connections to eastern peoples. Much of this is speculation, connecting these references by inference. There is no certainty in making these connections only that it is evident that there are connections.

An alternate hypothesis brought forward in a documentary film about Irish-Celtic connections to North-African and Middle-Eastern origins in the Atlantean quartet series by Bob Quinn, an Irish filmmaker, explores connections between Irish and eastern music in a rather convincing manner. The film, made in 1983, draws strong parallels from numerous examples of Irish and eastern music. Quinn's original idea has gained some academic credibility over the last forty years or so, from scholars such as Barry Cunliffe.

"The project began innocently enough when, nearly thirty years ago, an Irish film maker, Bob Quinn, set out to show that the singing style of his neighbours in Gaelic-speaking Conamara in the West of Ireland was much more than a debased and incomprehensible version of ballad-singing - which was the attitude of anglophones.

Over the following thirty years he showed how similar it was to North African and Afro-Asian singing and daringly went on to discover historic, religious, artistic, archaeological and linguistic similarities with Hamito-Semitic cultures".

But this is still not the last word ...

"Other theories, not necessarily in conflict with this, point to ‘gypsy’ or Roma influence. Travelling people whose journey took them through the Ottoman Balkans or Moorish Spain, brought the exciting and dynamic sounds of the Muslim world to add spice to the local British musical menu". (Celtic Fringe and Muslim Heart)

The traditional accounts are constantly being challenged. New sources and the ability to connect them together in new ways point to a very substantial Celtic culture. It is important to consider these accounts in context, that is to say, incompleteness. So any re-assemblage of the historical record is, therefore, incomplete. Yet, the record shows that Celtic culture was present and active throughout Europe and for quite a long time. Language, culture or race don't appear to be barriers to the widespread dispersal of Celtic expression.

A big question is to how the language may have dispersed without dispersal of DNA or family names. It might have been related to trade, where smaller groups learn the language of the dominant group, in order to facilitate a trade network.

Importantly, even with all the effort being applied to understanding the dispersal of Celtic language and culture, no hypothesis is so dominant as to entirely eclipse the others. Very much is still being debated and is not fully understood, awaiting new discoveries. For instance, the question of how Celtic language may have dispersed into Spain, or ultimately the British Isles, with little or no evidence of dispersal of DNA has not been answered.

What took place in most of Europe during the Roman conquest forced Celtic peoples from their homelands. They ended up not only surviving but developing rich and varied cultures in those fringe regions where the Roman influence did not reach. The most important remnants of what must have been a pervasive Celtic musical tradition are in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany and Galicia. However, these are not the origins. We'll never know if any hand-me-down is complete or even if they got it right — in the end something old is now new again, and again.

Today's Celtic Music

'Celtic music', as we know it today, defies definition and many popular forms of modern music are descended from it. ... From soft harmonies to whisky infused rock - from stories to protests to the man on the street ... definitely not what ... or where ... you might expect ... Where is this going? Well, just about anywhere! ...

Celtic music - Wikipedia

Artists vary from Alan Doyle to Alan Stivell to Celtic Woman to Clannad to The Chieftains to The Dropkick Murphys to Enya to Lorena McKennitt to The Killdares to Miracle Of Sound

Celtic music: Introduction | Artists | Instruments (Pages date from 2006)

Alfredo De Pietra, the author of this web site is/was a writer for The Celtic Cafe, the most important web site of Celtic music and Keltika, the monthly Italian magazine about Celtic music and culture but neither site is available. He also collaborates in the Celtic World project. Hear his guitar work on soundcloud.

Celtic festivals - Wikipedia

Celtic Fringe and Muslim Heart

A production company called Mishkat Media has released a music album which seems improbably ambitious: a sequence of translated Persian and Arabic songs, sung in English, to Celtic tunes. Sceptics are going to shake their heads and insist that such a hybrid child could never live. But take a close listen and then ask this surprising question: are British and Islamic musical traditions in fact so very far apart?

Celtic music: Genres of influence, Tresbear Music, Dickson, TN

Celtic music, much like the Gypsy style or Roma music is hard to pin down or define in a very specific way. For one thing, Celtic music can mean different things in different countries. In general, it covers the traditional music of the Celtic nations – Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany (France), Galicia (Spain) along with other areas heavily influenced by the Celts, such as the U.S. and the maritime provinces of Canada, as well as some newer music based on traditions from these countries.

Breton musicians frequently play in Irish or Scottish music and at least one modern Galician group (Milladoiro) sounds quite Irish. In Canada and the US, the traditions are much more mixed, and it is there that the term Celtic is most used, though many groups from particular Celtic regions play music from other regions as well.

The name Celtic music is itself sometimes controversial. For starters, the Celts as an identifiable race are long gone. There are strong differences between traditional music in the different Celtic countries, and many of the similarities are due to more recent influences. Also, to some, the word Celtic connotes Celtic mysticism and/or new-age music, which have little, if anything, to do with traditional Celtic music.

The term Celtic music is perhaps most often applied to the music of Ireland and Scotland because both have produced well-known, distinctive musical styles which share common features and mutual influences. In general, the strongest connections are between Irish and Scottish music traditions in the context of all areas considered to be Celtic nations. The definition is further complicated by the fact that Irish independence has allowed Ireland to promote ‘Celtic’ music as a specifically Irish product. However, these are modern geographical references to a people who share a common Celtic ancestry and consequently, a common musical heritage.

It is also worth remembering that even a term such as Irish traditional music is a lumping together of many different styles, from the raw, Scottish-tinged music of Donegal to the lyrical, easy-going style of Clare and many other regional styles that are only partly compatible.

Celtic punk

Celtic punk is punk rock mixed with traditional Celtic music.

Celtic punk bands often play traditional Irish, Welsh or Scottish folk and political songs, as well as original compositions. Common themes in Celtic punk music include politics, Celtic culture and identity, heritage, religion, drinking and working class pride.

The genre was popularized in the 1980s by The Pogues. ... Or get an earful from The Rumjacks, out of Sydney - Australia! ... Or catch the vibe close to where it may have started in Italy, with The SIDH

Celtic rock

Celtic rock is a genre of folk rock, as well as a form of Celtic fusion which incorporates Celtic music, instrumentation and themes into a rock music context. It has been extremely prolific since the early 1970s and can be seen as a key foundation of the development of highly successful mainstream Celtic bands and popular musical performers, as well as creating important derivatives through further fusions. It has played a major role in the maintenance and definition of regional and national identities and in fostering a pan-Celtic culture. It has also helped to communicate those cultures to external audiences.

Notably, the Celtic rock movement encompasses a wide range of styles, expressions and countries that broaden the entire reach of Celtic music. Not unlike the music's history stretching over centuries and numerous geographic regions, ultimately taking in a broad cross-section of peoples and linguistic groups.

Festival Interceltique de Lorient | Brittany tourism

Each summer, around 700,000 people from all over the world invade the Celtic land of Lorient for the Festival Interceltique. From Galicia to Scotland.

History of Celtic Music, Celtic Life International, 2020

Celtic music is a broad grouping of musical genres that evolved out of the folk musical traditions of the Celtic peoples of Western Europe. The term Celtic music may refer to both orally-transmitted traditional music and recorded popular music with only a superficial resemblance to folk styles of the Celtic peoples.

Most typically, the term Celtic music is applied to the music of Ireland and Scotland, because both places have produced well-known distinctive styles which actually have genuine commonality and clear mutual influences. The music of Wales, Cornwall, Isle of Man, Brittany, Northumbria and Galicia are also frequently considered a part of Celtic music, the Celtic tradition being particularly strong in Brittany, where Celtic festivals large and small take place throughout the year. Finally, the music of ethnically Celtic peoples abroad are also considered, especially in Canada and the United States.

Introduction: Locating Celtic Music (and Song) by James Porter, 1998, History, Western Folklore

The first issue, then-supposing that the concept of "Celtic music" is a valid one-is its ambiguity of reference in comparison with "Celtic song," which would presumably allude to songs in a Celtic language. Older rural concepts contrasted music and song more readily than newer urban contexts, in which a healthy middle ground of song with instruments has developed, particularly since the eighteenth century. "Celtic music" justifiably applies to such practice as much as to solo or concerted instrumental music. And "Celtic music," as it is understood in today's urbanised world, can and does include song in popular usage. As a consequence, the second issue involves a widespread conception of Celtic music which not only signifies different things to different people even within the same country or culture area-but has an air of insubstantiality about it. Hence the "locating" as the title of this journal issue. But there is also the more complex issue of whether any music made by indigenous musicians in a country with a living Celtic language can be called "Celtic," whether "classical" or "popular" (e.g., Irish country-and-western).

National Identity and Popular Music: Questioning the ‘Celtic’ by Alistair Mutch, Nottingham Trent University, 2009

The term ‘Celtic’ is encountered in a variety of contexts when exploring a range of cultural and social concerns. ... The term ‘Celtic’ risks an essentialist approach

which both masks the very different traditions within Scotland and does not help in explaining the emergence of distinctively British forms of music.

This article focuses on the contributions of two artists, Ian Anderson and Richard Thompson, whose music is often seen as primarily English.

What is celtic music

The term 'celtic music' is a rather loose one ... and ... is sometimes controversial. Historically the celtic races covered much of Europe, but their last strongholds were in the west, where their traces still linger in language and other aspects of culture.

Instruments

Drums, flutes and stringed instruments have existed for millenia. Little is known about early adaptations of these instruments. It is certainly plausible that the music of early cultures have adapted them in ways we know very little about.

Bagpipes - Wikipedia

Bagpipe - Musica Antiqua - U Iowa

The origins of the bagpipe can be traced back to the most ancient civilizations. The bagpipe probably originated as a rustic instrument in many cultures because a herdsman had the necessary materials at hand: a goat or sheep skin and a reed pipe. The instrument is mentioned in the Bible, and historians believe that it originated in Sumaria. Through Celtic migration it was introduced to Persia and India, and subsequently to Greece and Rome. In fact, a Roman historian of the first century wrote that the Emporer Nero knew how to play the pipe with his mouth and the bag thrust under his arm. During the Middle Ages, however, the bagpipe was heard and appreciated by all levels of society.

Bagpipes have always been made in many shapes and sizes, and have been played throughout Europe from before the Norman Conquest until the present day. Medieval pipes usually had a single drone - see contemporary illustrations of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales for English single-drone pipes. Around 1400 (give or take 50 years), most shepherd-style pipes acquired a second drone. A third drone is added about after 1550. See paintings by Brueghel and the illustrations in Praetorius' Syntagma Musicum. The Renaissance also saw the advent of small, quiet chamber pipes such as Praetorius' Hummelchen or the French shuttle-drone models, some blown with bellows under the arm rather than with the mouth.

[ Note: Other illustrations exist, by Albrecht Durer and ter Brugghen ]

Brief History of the Bagpipes

Bagpipes are thought to have been first used in ancient Egypt.

The bagpipe was the instrument of the Roman infantry while the trumpet was used by the cavalry.

Bodhrán: its origin, meaning and history by Liam Ó Bharáin, Comholtas, Treior, November, 2007

The bodhrán is a single headed frame drum of a general type that is widespread within the traditional music of western Asia and south India, parts of eastern Europe, north Africa, Iberia, Ireland and Brazil, and occurs sporadically in other cultures, for example, aboriginal Americans the Inuit and in Tibet and Mongolia (cf. Sachs, 1942; Blades, 1970; McCrickard, 1987). In mainstream western culture it is chiefly represented by the tambourine. The bodhrán is a very basic type of drum; does not normally have jingles or snares attached. It is perhaps best defined among its type by the playing style, being played predominantly with a single stick or beater and traditionally used as an accompanying instrument following the rhythm of the music as closely as possible.

Bouzouki - Wikipedia

The Greek bouzouki is a plucked musical instrument of the lute family, called the thabouras or tambouras family. The tambouras existed in ancient Greece as the pandoura, and can be found in various sizes, shapes, depths of body, lengths of neck and number of strings. The bouzouki and the baglamas are the direct descendants. The Greek marble relief, known as the Mantineia Base (now exhibited at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens), dating from 330–320 BC, shows a muse playing a variant of the pandoura. ... The Irish bouzouki, with four courses, a flatter back, and differently tuned from the Greek bouzouki, is a more recent development, stemming from the introduction of the Greek instrument into Irish music by Johnny Moynihan around 1965. It was subsequently adopted by Andy Irvine, Dónal Lunny, and many others, although some Irish musicians, such as the late Alec Finn, continued to use the Greek-style instruments.

Cittern - Wikipedia

The cittern or cithren is a stringed instrument dating from the Renaissance. Modern scholars debate its exact history, but it is generally accepted that it is descended from the Medieval citole (or cytole). It looks much like the modern-day flat-back mandolin and the modern Irish bouzouki, and is descended from the English guitar. Its flat-back design was simpler and cheaper to construct than the lute. It was also easier to play, smaller, less delicate and more portable. Played by all classes, the cittern was a premier instrument of casual music-making much as is the guitar today. [Note: It is not weel known how widespread the use of the cittern was.]

The citole was a string musical instrument, closely associated with the medieval fiddles (viol, vielle, gigue) and commonly used from 1200–1350. ... In the citole entry in the 1985 edition of the New Grove Dictionary of Musical instruments, musicologist Laurence Wright said that there was plentiful evidence of the citole originating in either Italy or Spain and moving northward.

[ These stringed instruments were, in turn, descended from, or at least related to the cytara and the rotta, both dating to ancient times. The development of these portable stringed instruments ultimately led to the guitar, which was sometimes played with a bow, like a viola.

These instruments were, in turn, related to

even more ancient instruments: the lyre and also possibly, the zither.

So, while the Greeks are generally credited with inventing the lyre, there is a possibility that it was introduced to them from elsewhere. "The instrument is frequently depicted in all forms of Greek art and the earliest examples date from the middle Bronze Age (c. 2000 BCE) in the Cycladic and Minoan civilizations". (The Lyre (worldhistory.org)) ]

Irish fiddle

The Celtic fiddle is one of the most important instruments in the traditional repertoire of Celtic music. The fiddle itself is identical to the violin, however it is played differently in widely varying regional styles. In the era of sound recording some regional styles have been transmitted more widely while others have become more uncommon.

Rattles

Ocasionally, rattles appear in musical expression. "The use of rattles in folk dances and rituals is recorded in cultures throughout the world, either hand-held or attached to ceremonial costumes to dictate the rhythm of ritual dances, and to summon or repel supernatural beings or demons." (CHASING DEMONS – Celtic Ritual Rattles, Brendan MacGonagle)

Traditional Celtic Instruments

Celtic music is known by its unique instruments, from the airy wooden flute to the fiddle, all these instruments have one thing in common: they all make really good music. Let’s take a look at some of the Celtics musical instruments.

The instruments of celtic music

Celts - Wikipedia

This article is about the ancient and medieval peoples of Europe.

The earliest undisputed examples of Celtic language are the Lepontic inscriptions from the 6th century BC. Lepontic is an ancient Alpine Celtic language that was spoken in parts of Rhaetia and Cisalpine Gaul (what is now Northern Italy) between 550 and 100 BC. Lepontic is attested in inscriptions found in an area centered on Lugano, Switzerland, and including the Lake Como and Lake Maggiore areas of Italy.

Continental Celtic languages are attested almost exclusively through inscriptions and place-names. Insular Celtic languages are attested from the 4th century AD in Ogham inscriptions, although they were clearly being spoken much earlier. Celtic literary tradition begins with Old Irish texts around the 8th century AD. Elements of Celtic mythology are recorded in early Irish and early Welsh literature. Most written evidence of the early Celts comes from Greco-Roman writers, who often grouped the Celts as barbarian tribes. They followed an ancient Celtic religion overseen by druids.

The Celts were often in conflict with the Romans, such as in the Roman–Gallic wars, the Celtiberian Wars, the conquest of Gaul and conquest of Britain. By the 1st century AD, most Celtic territories had become part of the Roman Empire. By c.500, due to Romanization and the migration of Germanic tribes, Celtic culture had mostly become restricted to Ireland, western and northern Britain, and Brittany. Between the 5th and 8th centuries, the Celtic-speaking communities in these Atlantic regions emerged as a reasonably cohesive cultural entity. They had a common linguistic, religious and artistic heritage that distinguished them from surrounding cultures.

Insular Celtic culture diversified into that of the Gaels (Irish, Scots and Manx) and the Celtic Britons (Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons) of the medieval and modern periods. A modern Celtic identity was constructed as part of the Romanticist Celtic Revival in Britain, Ireland, and other European territories such as Galicia. Today, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, and Breton are still spoken in parts of their former territories, while Cornish and Manx are undergoing a revival.

"The debate between the two major competing explanations for Indo-European’s origins and spread, the Anatolian and Steppe hypotheses, is considered one of the biggest disagreements in scholarly understandings of Celtic origins ... The Anatolian hypothesis attaches Indo-European language onto the spread of agriculture into Europe from Anatolia starting around 6000 BCE, reaching the British-Irish isles around 4000 BCE ... The Steppe hypothesis holds that Indo-European language spread outwards from the Pontic-Caspian steppes, see Figure 5, from around 5000 BCE with the migrations of nomadic pastoralists ... The Steppe hypothesis was shown to have been a much more coherent model for Indo-European origins, enjoying multidisciplinary support".

Gallacher, Johnnie William. 2020. In: ‘Celtic origins: Archaeologically speaking’. In Joanna Kopaczyk & Robert McColl Millar (eds.) 2020. Language on the move across domains and communities. Selected papers from the 12th triennial Forum for Research on the Languages of Scotland and Ulster, Glasgow 2018. Aberdeen: FRLSU, pp. 174-199. ISBN: 978-0-9566549-5-3.

The Celts: A Very Short Introduction by Barry Cunliffe, Oxford University Press, 2003

"Celts are well and truly embedded in our everyday life – at least in popular perception. But there are other levels to this. Music, for example, is undergoing a Celtic renaissance, nowhere more impressive than in the Festival Interceltic de Lorient, heir to the Bagpipes Festival that was held at Brest from 1953 to 1970. Here, international groups, including The Chieftains and Gaelic Storm, play to the same audiences as Breton stars like Alan Stivell. Denez Prigent’s report in Carn of the 2001 Festival claimed attendances of 500,000: ‘going beyond the “folkloric” it has opened Breton music to the ocean winds and invited to its celebration all the scattered members of the great Celtic family’. At a less pop level, the compositions and performances of the Breton pianist Didier Squiben, blending the cadences and rhythms of traditional folk music with echoes of the wind and the sea, provide a vivid example of the vitality of modern music in its Celtic guise".

Language

The knowledge base of Indo-European languages and their expansion from a central region is well established, however the details are constantly being revised.

Celtic from the West 3 by John T. Koch and Barry W. Cunliffe, 2016:

Atlantic Europe in the Metal Ages ― Questions of Shared Language

"The Celtic languages and groups called Keltoi (i.e. 'Celts') emerge into our written records at the pre-Roman

This is not the only set of Palaeohispanic names with closer parallels in Brythonic and Goidelic than in Gaulish, which raises the interesting question of whether they represent peripheral survivals of usages that had declined in Gaul or evidence for direct contact by sea. One long-standing unresolved problem of IndoEuropean linguistics is whether the Celtic and Italic branches (the latter being the ancestral group of Latin) descend from a single protolanguage, ProtoItalo-Celtic. If this was the case, the implications would be incompatible with the idea that Celtic was an eastern Indo-European language as favoured by Isaac (2010) and the late K. H. Schmidt (2012). In Chapter 17 Peter Schrijver presents a linguistic case for an Italo-Celtic protolanguage. He finds the closest connections of Celtic with Venetic and Sabellian. On this basis he seeks the Proto-Celtic homeland in Italy and argues for an identification with the Canegrate Urnfield culture of the Italian Late Bronze Age c. 1300–1100 BC, situated north of the upper Po, thus overlapping the territory of the Lepontic inscriptions. This model implies subsequent expansions of Celtic ‘out of Italy’ to central Europe, Gaul, the Iberian Peninsula, Britain, and Ireland. The general editors note that the linguistic argument for an Italo-Celtic protolanguage is not otherwise seen as demanding a Celtic homeland in Italy. The Celtic from the West hypothesis also predicts shared innovations with Italic, as a neighbouring IE branch in south-western Europe, whether or not the branches had begun as a unified post-IE node".

An Alternative to ‘Celtic from the East’ and ‘Celtic from the West’ by Patrick Sims-Williams, Cambridge University Press, 02 April 2020

"A simpler hypothesis: Celtic from the centre

A more economical view of the origin of the Celtic languages, consonant with the historical and linguistic evidence, might run as follows (cf. Sims-Williams 2017a, 432–5).

Celtic presumably emerged as a distinct Indo-European dialect around the second millennium bc, probably somewhere in Gaul (Gallia/Keltikê), whence it spread in various directions and at various speeds in the first millennium bc, gradually supplanting other languages, including Indo-European ones—Lusitanian and ‘Eastern Alpine Indo-European’ are candidates—and non-Indo-European ones—candidates are Raetic, Aquitanian/Proto-Basque, ‘Iberian’, ‘Tartessian’ and Pictish (Rodway 2020; Sims-Williams 2012b, 431); and presumably there were dozens more languages about which we know nothing, especially in northern Europe.

The reasons for suggesting Gaul (perhaps including part of Cisalpine Gaul) are: (i) it is central, obviating the need to suppose that Celtic was spoken over a vast area for a very long time yet somehow avoided major dialectal splits (cf. Sims-Williams 2017a, 434); (ii) it keeps Celtic fairly close to Italy, which suits the view that Italic and Celtic were in some way linked in the second millennium (Schrijver 2016). During the first millennium bc, Celtic spread into eastern Iberia (probably well before the time of Herodotus and Herodorus), into northern Italy (as first evidenced by the Lepontic inscriptions in the sixth century: Stifter 2019), into Britain, and perhaps already into Ireland (though Ireland is undocumented), and also towards the east, eventually reaching Galatia in Turkey in the third century bc (as documented in Greek sources).

The Celts who took their language with them may often have adopted the material culture of the territories where they settled, thereby becoming archaeologically indistinguishable. At least latterly, some large-scale folk movements were involved, judging by the classical sources, but Celtic may also have spread incrementally and unspectacularly, following the model proposed by Robb (1991, as discussed by Sims-Williams 2012b, 436; cf. Mallory 2016; Wodtko 2013, 193–204). Since Celtic may well have been moving into areas with patchworks of minor languages—5000 speakers being the median for languages worldwide (Nettle 1999, 113)—quite a low number of Celtic speakers could be enough to effect a language shift. For example, if only 10 per cent of people in Britain spoke Celtic but the rest of the population spoke a dozen other languages, Celtic might have the advantage, especially when reinforced by the language of the adjacent part of the Continent.

Finally, in the latter part of the first millennium bc, Celtic may still have been expanding and consolidating in many areas, both east and west, before it was overtaken by the expansion of the Roman Empire.

‘Celtic from the Centre’ may lack the time-depth and exotic locations that appeal to romantics, but the economical hypothesis sketched above is realistic and fits the known facts. According to Caesar, central France was occupied by the Galli (Gauls), who called themselves Celtae in their own language (Gallic War 1.1), and according to Livy it was the homeland of the Gauls who migrated to Italy (see Figure 1). It is an obvious place for Celtic ethnogenesis. That said, it must be admitted that while the most economical hypothesis is often the best available option, it is never necessarily correct. Even the above hypothesis entails a gap of perhaps a millennium between the hypothetical emergence of the Celtic language and its first attestation in the Lepontic inscriptions of the sixth century bc. Currently we have no direct linguistic evidence about what occurred during that gap".

1 Proto-Indo-European language - Wikipedia

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the theorized common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists.

2 Proto-Celtic language - Wikipedia

The Proto-Celtic language, also called 'Common Celtic', is the partially reconstructed proto-language of all the known Celtic languages. ... Proto-Celtic is a descendant of the Proto-Indo-European language and is itself the ancestor of the Celtic languages which are members of the modern Indo-European language family, the most commonly spoken language family. Modern Celtic languages share common features with Italic languages that are unseen in other branches and according to one theory they may have formed an ancient Italo-Celtic branch. The duration of the cultures speaking Proto-Celtic was relatively brief compared to PIE's 2,000 years. By the Iron Age Hallstatt culture of around 800 BC these people had become fully Celtic. Proto-Celtic is mostly dated to the Late Bronze Age, ca. 1200–900 BCE

3 Pre-Celtic - Wikipedia

The pre-Celtic period in the prehistory of Central Europe and Western Europe occurred before the expansion of the Celts or their culture in Iron Age Europe and Anatolia (9th to 6th centuries BC), but after the emergence of the Proto-Celtic language and cultures. The area involved is that of the maximum extent of the Celtic languages in about the mid 1st century BC. The extent to which Celtic language, culture and genetics coincided and interacted during this period remains very uncertain and controversial.

4 Celtic languages - Wikipedia

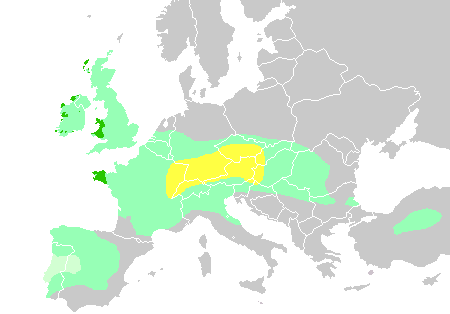

Celtic expansion in Europe -

the core Hallstatt territory, expansion before 500 BC -

maximum Celtic expansion by the 270s BC -

Lusitanian, Autrigones, Varduli and Caristi areas of Iberia, "Celticity" uncertain -

areas that remain Celtic-speaking today

The Celtic languages are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707, following Paul-Yves Pezron, who made the explicit link between the Celts described by classical writers and the Welsh and Breton languages.

During the 1st millennium BC, Celtic languages were spoken across much of Europe and central Anatolia. Today, they are restricted to the northwestern fringe of Europe and a few diaspora communities. There are four living languages: Welsh, Breton, Irish, and Scottish Gaelic.

5 Insular Celtic languages - Wikipedia

Insular Celtic languages are the group of Celtic languages of Great Britain, Ireland and Brittany.

Surviving Celtic languages are such, including Breton, which remains spoken in Brittany, France, Continental Europe; the Continental Celtic languages are extinct in the rest of mainland Europe, where they were quite widely spoken, and in Anatolia.

Related branch:

Iranian languages - Wikipedia

The Iranian languages all descend from a common ancestor: Proto-Iranian which itself evolved from Proto-Indo-Iranian. This ancestor language is speculated to have origins in Central Asia, and the Andronovo Culture is suggested as a candidate for the common Indo-Iranian culture around 2000 BC.

Geography

The Indo-European migrations started c. 4200 BC. through the areas of the Black sea and the Balkan peninsula in East and Southeast Europe. In the next 3000 years the Indo-European languages expanded through Europe.

source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Europe

Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex - Wikipedia

Hallstatt - Wikipedia

Pontic-Caspian steppe (region) - Wikipedia

Timeline

The Kurgan hypothesis (also known as the Kurgan theory or Kurgan model) or Steppe theory is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and parts of Asia.[3] It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

4500–4000: Early PIE. Sredny Stog, Dnieper–Donets and Samara cultures, domestication of the horse (Wave 1).

4000–3500: The Pit Grave culture (a.k.a. Yamnaya culture), the prototypical kurgan builders, emerges in the steppe, and the Maykop culture in the northern Caucasus. Indo-Hittite models postulate the separation of Proto-Anatolian before this time.

3500–3000: Middle PIE. The Pit Grave culture is at its peak, representing the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols, predominantly practicing animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillforts, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers. Contact of the Pit Grave culture with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the "kurganized" Globular Amphora and Baden cultures (Wave 2). The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the beginning Bronze Age, and Bronze weapons and artifacts are introduced to Pit Grave territory. Probable early Satemization.

3000–2500: Late PIE. The Pit Grave culture extends over the entire Pontic steppe (Wave 3). The Corded Ware culture extends from the Rhine to the Volga, corresponding to the latest phase of Indo-European unity, the vast "kurganized" area disintegrating into various independent languages and cultures, still in loose contact enabling the spread of technology and early loans between the groups, except for the Anatolian and Tocharian branches, which are already isolated from these processes. The centum–satem break is probably complete, but the phonetic trends of Satemization remain active.

The rapidly developing field of archaeogenetics and genetic genealogy since the late 1990s has not only confirmed a migratory pattern out of the Pontic Steppe at the relevant time, it also suggests the possibility that the population movement involved was more substantial than anticipated and invasive.

[ Whether one agrees with or disputes this theory, it clearly demonstrates that there was possibilities for widespread exchanges of people, ideas and technology throughout the continent and over extensice timespans. ]

Cultures

Cultural horizons overlap geographic regions and historical periods - there is not any clearly defined transition from one culture to another. Further, definitions of timelines and geographic boundaries are based on discoveries which cannot allow for as yet undiscovered artefacts. Our understanding of early European identity is evolving rapidly.

Western Steppe Herders

c. 4000 to 1000 BCE

Very recent studies are pointing towards a single region as the source for Indo-European languages in Europe.

Yamnaya culture (Pit Grave culture)

c. 3400–2600 BC

According to Anthony (2007), the early Yamnaya horizon spread quickly across the Pontic–Caspian steppes between c. 3400 and 3200 BC.

Corded Ware culture

circa 2900 BC – circa 2350 BC

The Corded Ware culture may have played a central role in the spread of the Indo-European languages in Europe during the Copper and Bronze Ages. According to Mallory (1999), the Corded Ware culture may have been "the common prehistoric ancestor of the later Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, and possibly some of the Indo-European languages of Italy."

Bell Beaker culture

c. 2800–1800 BC

Bell Beaker people took advantage of transport by sea and rivers, creating a cultural spread extending from Ireland to the Carpathian Basin and south along the Atlantic coast and along the Rhône valley to Portugal, North Africa, and Sicily, even penetrating northern and central Italy. (Barry Cunliffe)

The Bell Beaker phenomenon

The Bell Beaker phenomenon was not an ethnic culture like most other archeological cultures of the period, but rather represents a huge multicultural trade network inside which a variety of new artefacts, customs and ideas were exchanged and diffused, notably metalwork in copper, bronze and gold and archery.

Únětice culture

c. 2300–1800 BC

Recently, the Únětice culture has been cited as a pan-European cultural phenomenon whose influence covered large areas due to intensive exchange, with Únětice pottery and bronze artefacts found from Ireland to Scandinavia, the Italian Peninsula, and the Balkans. As such, it is candidate for a late community connecting a continuum of already scattered North-West Indo-European languages ancestral to Italic, Celtic, and Germanic, and perhaps Balto–Slavic, where words were frequently exchanged and a common lexicon and certain regional isoglosses were shared.

Tumulus culture

c. 1600 to 1200 BC

The culture's dispersed settlements centred in fortified structures.

Andronovo culture (Indo-Iranian)

c. 2000 BC – 900 BC

Being nomadic, some of these peoples migrated largely in a easterly direction.Karasuk culture (Eastern part of Andronovo culture)

ca. 1500–800 BC

Urnfield culture

c. 1300 — c. 750 BC

The Urnfield culture grew from the preceding Tumulus culture.

The Urnfield culture (c. 1300 BC – 750 BC) was a late Bronze Age culture of Central Europe, often divided into several local cultures within a broader Urnfield tradition. The name comes from the custom of cremating the dead and placing their ashes in urns which were then buried in fields.

Some linguists, such as Peter Schrijver, have suggested that the people of this area may have spoken a form of Italo-Celtic, and suggest that the Proto-Celtic language may originate from a north-western Italian dialect of this language family.

Hallstatt culture

1200 – 500 BC

Hallstatt was a very wealthy culture, based on the salt mine and trade extended over a wide area, including with the Greeks. The settlements were mostly fortified, situated on hilltops, and frequently included the workshops of bronze-, silver-, and goldsmiths. It is probable that some if not all of the diffusion of Hallstatt culture took place in a Celtic-speaking context. The Lepontic Celtic language inscriptions of the area show the language of the Golasecca culture was clearly Celtic making it probable that the 13th-century BC precursor language of at least the western Hallstatt was also Celtic, or a precursor to it.

Two artifacts clearly show musicians playing their instruments, both dating from around 500BC. One artifact, discovered in Slovenia, the Vače Situla (Wikipedia) depicts a group of revellers that "comprises one man seated on a throne and playing a Panpipe, with a bareheaded servant offering him drink from a situla".

While, the "presence of some celtic graves by the alpine wayside is not enough to demonstrate the Celtics formed a dominating rank over the venetic inhabitants, but it can only prove the local activity of celtic artisans and merchants. In fact, the evidences' examination demonstrates the great preponderance of the venetic culture"..

Another, the situla of Certosa, found near Bologna, depicts "two venetic nobles play traditional instruments, zither and panpipes, sat upon a settee, while two dancers jump over wolf's head-shaped backs (Bompiani)". (The Situla and the Ancient Veneti: Explanation to images)

La Tène culture

circa 450 BCE. — circa 1 BCE

Artefacts typical of the La Tène culture were also discovered in stray finds as far afield as Scandinavia, Northern Germany, Poland and in the Balkans. It is therefore common to also talk of the "La Tène period" in the context of those regions even though they were never part of the La Tène culture proper, but connected to its core area via trade.

Followed by Roman imperial period

"The poetry was of the bardic type, and consisted in great part of eulogies and elegies extolling the virtues of heroic leaders and warriors. This trend continued in Scots Gaelic poetry until the 18th century AD" (La Tène @ GlenCelt)

Re-approaching Celts: Origins, Society, and Social Change by Rachel Pope, 2020

"Having improved our understanding of the historical Celts, we find that the archaeology, texts, and linguistics finally converge, so too the aDNA. Celtic language is now believed to have Bronze Age roots in Gaul. Early Celtic (Venetic, Lepontic) is found in North Italy, with fragments now claimed also in southwestern Spain: each might now receive a cautious seventh century BC date. The growth of “Celtic proper”—a phenomenon of the Celtic migrations (actually the descendants of the Celts)—is seen farther west in the third century BC (Spain, Britain) as well as east to Galatia (Cunliffe and Koch 2019; Sims-Williams 2020). Important to this work is an understanding that people, in a myriad of social networks communicate, travel, and integrate, meaning that traditions ultimately shift, typically over centuries, and societies change—Late Hallstatt society lasted 200 years, Jogassian 150 years. The past is a continuous coming and going of individuals and small groups, that is how metal and burial rites shifted east as ceramics shifted west (Collis 2003, p. 188). Movement was small-scale over time (Cunnington 1923). Even the migrations to North Italy took place over 200 years. Social transitions typically take time; the demise of Hallstatt traditions took three to four generations, and Greek texts display a 60-year time lag in knowledge".

Documentaries

Barry Cunliffe - Who Were the Celts - YouTube

Until recently it used to be thought that they emerged in Eastern France and Southern Germany and spread westwards to Spain, Brittany, Britain and Ireland taking their distinctive language with them which survives today as Breton, Welsh, Gaelic and Irish. But recent work is suggesting that the Celtic language may have developed in the Atlantic zone of Europe at a very early date, and DNA studies offer some support to this. So who were the Celts? We will explore the evidence and try to offer an answer.

Irish-Celtic connections to North-African and Middle-Eastern origins by Bob Quinn - YouTube

The Ancient Celts with Barry Cunliffe - Episode 41 — The Archaeology Show, ArcheoWebby, May 5, 2018 (podcast)

Sir Barry Cunliffe returns for the third time to The Archaeology Show! On today's show, we talk to him about the Ancient Celts and the second edition of the book with the same name. Archaeologists have learned a lot about the ancient Celts since the first edition of the book was released and we scrape the surface on this show.

The Celts - BBC Series, Episode 1 - In the Beginning - YouTube

The Celts - In Our Time, - BBC Radio 4, 21 Feb 2002 (audio)

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Celts. Around 400 BC a great swathe of Western Europe from Ireland to Southern Russia was dominated by one civilisation. Perched on the North Western fringe of this vast Iron Age culture were the British who shared many of the religious, artistic and social customs of their European neighbours. These customs were Celtic and this civilisation was the Celts.The Greek historians who studied and recorded the Celts' way of life deemed them to be one of the four great Barbarian peoples of the world. The Romans wrote vivid accounts of Celtic rituals including the practice of human sacrifice - presided over by Druids - and the tradition of decapitating their enemies and turning their heads into drinking vessels.But what were the Celts in Britain really like? Was their apparent lust for violence tempered by a love of poetry and beautiful art? How far should we trust the classical historians in their writings on the Celts? And what can we learn from the archaeological remains that have been discovered in this country? With Barry Cunliffe, Professor of European Archaeology at Oxford University; Alistair Moffat, Historian and author of The Sea Kingdoms - The Story of Celtic Britain and Ireland; Miranda Aldhouse Green, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Wales.

"the celtic language evolved as a very much a lingua franca for trade and exchange and not just for trade and exchange of materials but for trade and exchange of ideas and technologies and belief systems - that's why the language as a unifier has got to be seen alongside technology and belief systems" (15:58ff Barry Cunliffe)